Choose Your Own (Negotiation) Adventure

Jack has been freelancing for six months. He’s done his fair share of work on spec and picked up jobs that friends and acquaintances didn’t want. He’s had some good experiences and some that made him long for the days he worked at Borders endlessly stocking Twilight novels.

Last week Jack got an email from an educational book publisher asking if he’d be interested in signing on for a three story job. It’s a basic work made for hire arrangement, but the pay will cover all of his rent and food expenses for the next two months, plus it’s with an editor he’s heard is fun to work with.

Jack diligently read through the contract and asked for changes to about 11 of the 12 contract provisions. Some changes were small and others were more significant, some he asked for just to see if he could get them. Today Jack got a reply back from the company’s contract manager. She accepted the changes he made to the spelling of his name, but rejected everything else.

What should Jack do?

If you think Jack should reply back providing a detailed argument for why he should receive every single solitary thing he asked for, including grammatical corrections, click here.

If you think Jack should cut his losses and reply back with a signed copy of the contract attached, click here.

If you think there is possibly a better, more reasonable choice Jack could make, click here.

______________________________________

When you’ve started taking negotiations seriously, the inclination to argue over everything you object to in a deal is fairly strong. And by “fairly strong” I mean, “tsunami-like.” The same thing probably happened when you began learning French or took up karate: you wanted to use your newfound skills as often as you possibly could. And so you startled the French foodcart guy by ordering your lunchtime crêpe au frottage and practiced the horse stance when idly talking with friends at a party.

As with French and karate, you must find that awkward balance between practice and restraint in order to foster your newfound negotiation skills.

Jack did the exact right thing in marking up the contract to address all of his concerns the first time around. But now that he’s gotten it back, and he can see how flexible the other side is (not very), he needs to step back and prioritize before moving forward. He’s not giving up on arguments. He’s focusing his energy on the arguments that are going to provide him with the most valuable results.

If you argue every point in a deal with the exact same fervor, you will weaken your best arguments and sap your energy for the real work that lies ahead. Make the other side take you seriously by focusing their attention on the areas that are most important. Accept those things that aren’t going to have a huge impact on your success and really fight for the things that will. You can even use the things you accept to your advantage by trading them for other things you want, e.g. “I can accept the liability requirements if you can agree to net 15 payment terms.”

Remember: you aren’t a professional negotiator. You’re a professional artist, writer, actor, designer, programmer or consultant. Spend your energy negotiating the things that will have the biggest and best impact on your career and let go of the rest.

________________________________

Trying out your negotiation chops the first few times can be pretty intimidating, too. If it’s something that doesn’t come naturally to you, negotiation can feel clumsy and forced. It’s normal to feel scared that you’re going to lose work by being pushy or asking too many questions. Until you’ve had enough practice to find a negotiation style that fits you well, the desire to cut your losses when you don’t get what you want is very strong. Resist.

Negotiations are conversations to learn what the other side cares about. Each move that a party makes in a negotiation is either

*a statement about what they care about; or

*a question of what the other side cares about.

Jack’s initial response to the company’s boilerplate contract was a statement about what his interests were. Because it’s the beginning of the conversation, it makes sense that Jack’s statement is fairly broad. The company’s response to Jack isn’t fundamentally different from the contract they originally sent him. Because their response doesn’t offer new information, don’t treat it like a statement, treat it like a question.

In this instance, it’s fairly safe to read the company’s response as, “Ok, but what do you really care about?” It’s a lot of work for the company to go through and provide thoughtful responses to each of Jack’s requests; they probably have a dozen similar contracts that they’re working on right now. It’s more efficient for them to make Jack do the work of highlighting where their differences actually lie. And if Jack doesn’t do the work and just returns the contract, they haven’t lost anything.

If you’re in a negotiation and the response you receive doesn’t seem to take into account what you just said, figure out why. Resist the urge to throw in the towel and be done with it. See if there isn’t a question hidden in what the other side is saying. If you can’t find one, ask a question of your own to determine what’s going on.

______________________________

Of course, choices in a negotiation are rarely so obvious and simple. Last week you may have been filled with level-headed confidence and today you might be too scared to open your front door. Congratulations! You live in the real world!

No matter how skilled you become as a negotiator, there will be days that you’ll want to fight someone tooth and nail and days where you’ll want to just have the whole thing over already. That’s OK. What’s not OK is thoughtlessly giving into to either urge.

If you find yourself wanting to take the extreme choice in a negotiation, ask yourself why. If you want to do it because it is the best thing for the deal, that’s one thing. But if you want to do it because of how you feel about the negotiation or the other side, it’s time to take a break. Give yourself some distance from the deal and don’t come back to it until you feel calmer.

Finding the right balance between arguing every point and giving in is a difficult process and sometimes it can take a long while to find a balance that suits you well. Help yourself get through that process by being aware of what you’re doing and making sure the choices you make support your goals.

And because Jack found the right balance for himself, he’s got a good job with a good editor at a rate he likes and a contract he trusts.

THE END

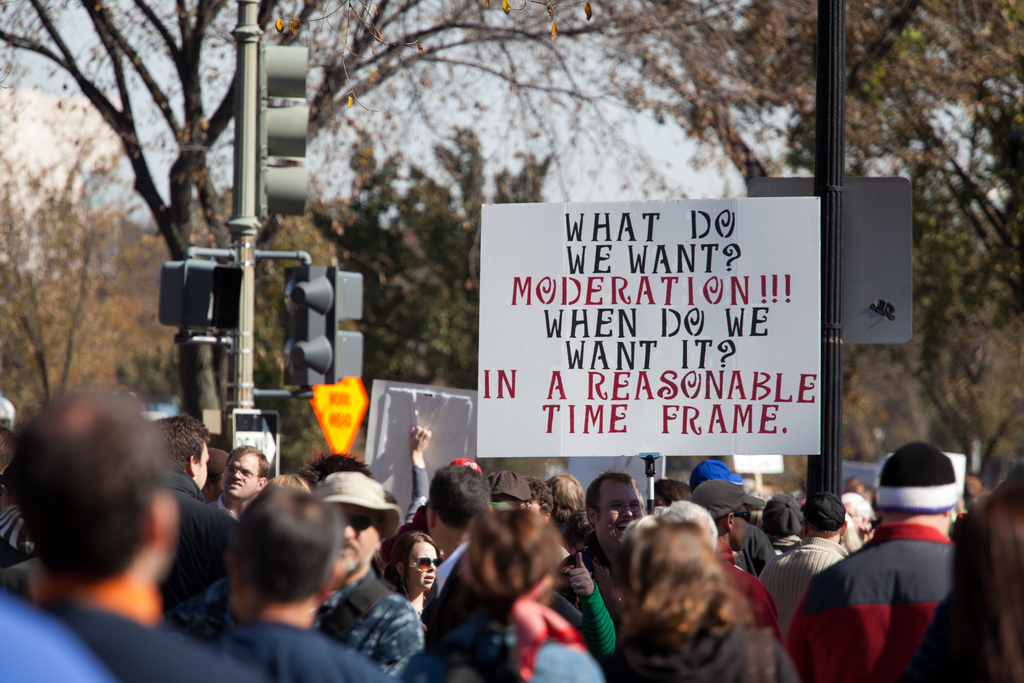

Featured image by Mr. Wright via Flickr.com.

Categories: Dealing with People